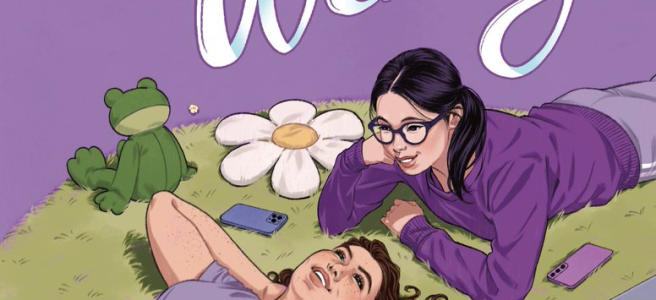

Yang, Kelly. Finally Heard. New York: Simon & Schuster Books for Young Readers, 2024.

ISBN-13: 978-1665947930 | $18.99 USD | 339 pages | MG Contemporary

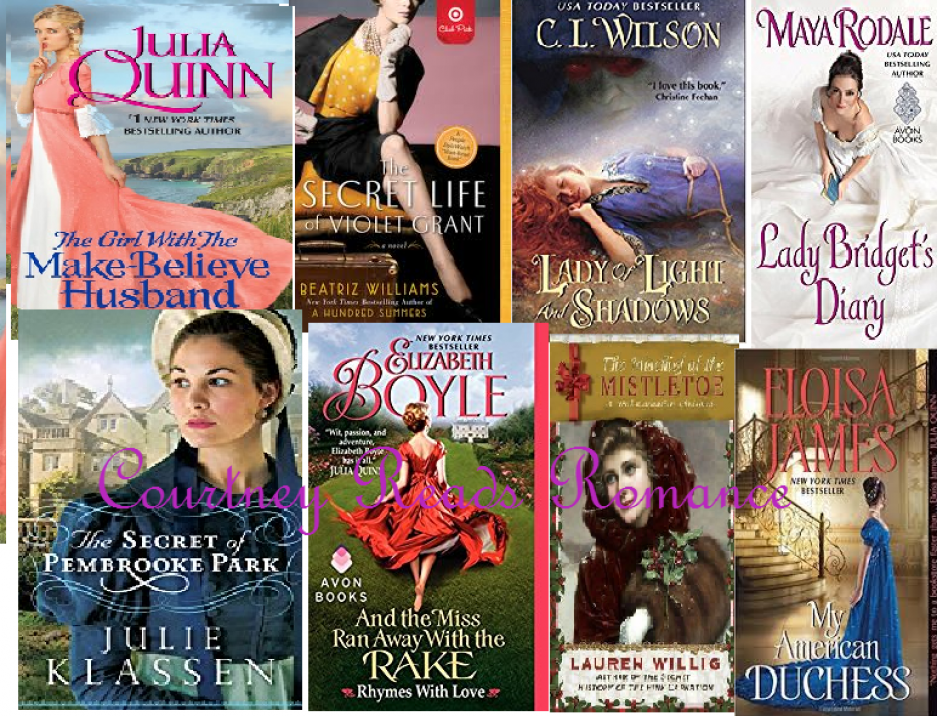

Blurb

From the New York Times bestselling author of Front Desk comes the sequel to Finally Seen in which Lina gets a phone and tries to navigate social media, only to discover not everything online is what it seems.

When ten-year-old Lina Gao sees her mom’s video on social media take off, she’s captivated by the potential to be seen and heard! Maybe online she can finally find the confidence she craves. Whereas in real life she’s growing so fast, she feels like microwave popcorn, bursting out of her skin!

With the help of her two best friends, Carla and Finn, and her little sister, Millie, Lina sets off to go viral. Except there’s a lot more to social media than Lina ever imagined, like:

1. Seeing inside her classmates’ lives!Is she really the only person on the planet who doesn’t have a walk-in closet?

2. Group chats! Disappearing videos!What is everyone talking about in the secret chats? And how can she join?

3. A bazillion stories about what to eat, wear, and put on her face. Could they all be telling the truth? Everyone sounds so sure of what they’re saying!

As Lina descends deeper and deeper into social media, it will take all her strength to break free from the likes and find the courage to be her authentic self in this fast-paced world.

In the series

#1 Finally Seen

Review

4 stars

I wasn’t anticipating a sequel to last year’s Finally Seen from Kelly Yang, but I was pleasantly surprised to hear about Finally Heard nonetheless. It was great to see Lina and Co. again, and see more of Lina’s growth in particular, especially as far it relates to the overall arc of the book this time around. She’s still dealing with a lot of similar challenges related to growing up, but there’s a new focus on cyberbullying, and how there’s an impact on her to the point where she fights back in a consequential way.

While issues with social media drama are almost ubiquitous at this point for all ages, I love that Yang chose to tackle it for a young audience, especially since I can’t think of many books tackling it in a way that is very relevant for the tween reader. But I love how it is also written in a way that speaks not just to them, but to their parents and families, especially by providing research and resources related to tweens and teens and social media at the end.

But even with the central narrative slowly escalating toward an intense confrontation, I still liked that there were some “fun” bits. With book banning being such a prominent theme in the prior book, I loved that this theme lived on in a love-fest for other middle grade and YA books, many of which I recognized. Yang even references another of her titles in-text, in a fun, meta bit of “book-ception.”

This was a great follow-up, and I’d recommend it to readers looking for an approachable story highlighting the dangers of social media for younger readers.

Author Bio

Kelly Yang is the New York Times bestselling author of Front Desk (winner of the 2019 Asian Pacific American Award for Children’s Literature), Parachutes, Three Keys, Room to Dream, New from Here, Finally Seen, and Finally Heard. Front Desk also won the Parents’ Choice Gold Medal, was the 2019 Global Read Aloud, and has earned numerous other honors including being named a best book of the year byThe Washington Post, Kirkus Reviews, School Library Journal, Publishers Weekly, and NPR. Learn more at KellyYang.com.

Buy links